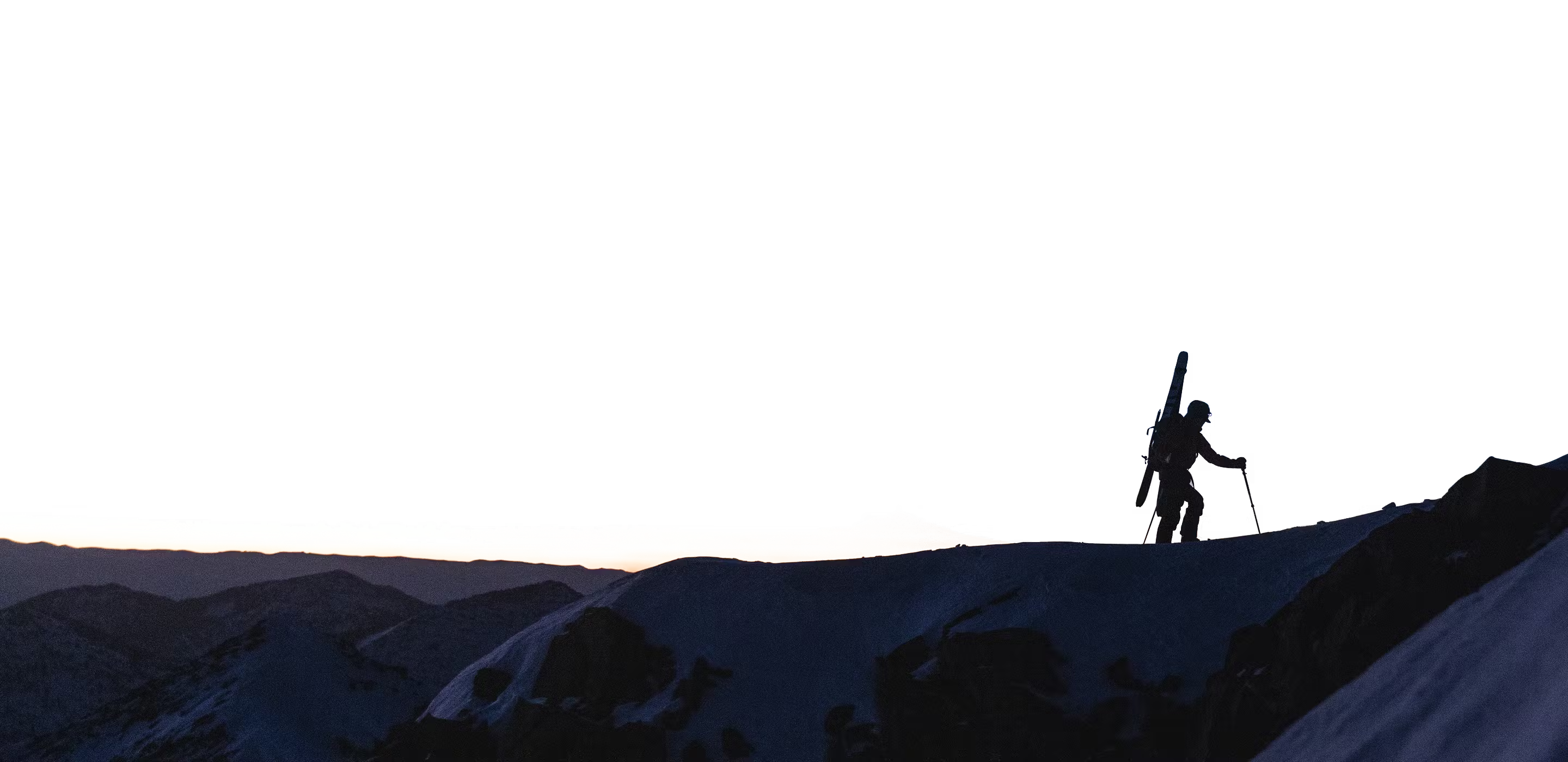

Photograph: Jason Hummel

Call of Sirens

DAWN ROSE SLOWLY on the morning of February 11, 2014. It was a Tuesday, though none of the eight skiers staying at the Schneider Cabin in Oregon’s Wallowa Mountains thought much about what day of the week it was. They were two days into a five-day backcountry hut trip, which meant two more full days of ski touring before they’d have to pack up and make the long haul back to the real world. The day before, they’d hiked and skied 3,000 vertical feet of excellent north-facing powder. And that morning there was another six inches of fresh outside the cabin, with more coming down.

It had been a weird and variable winter across the West. Ten people had already died in avalanches nationwide, four in just the last three days. In the Wallowas, a rugged playground of vertical granite and basalt with at least 31 peaks that rise above 9,000 feet, tucked away in northeastern Oregon, it’d been warm and then cold and then warm again, with early season snowfall significantly below average. Finally, at the end of January, the jet stream shifted south, bringing a steady winter cycle: 18 inches, then six, then another 18 to 23 as it grew progressively colder and drier. In the end, nearly four feet of new snow fell over 10 days at the Schneider Meadows SNOTEL plot, located at 5,400 feet, 1,800 feet below the old miner's cabin.

It was a big group: six clients and two guides. The clients—“guests” in the delicate parlance of outfitters—were each connected in one way or another to 26-year-old Quinton Dowling and his mother, Susan Polizzi, 60. The pair had both skied in the Wallowas before. Dowling worked for a medical research nonprofit in Seattle and was thinking about going to grad school. Polizzi was a longtime backcountry skier and outdoor enthusiast who'd worked as a nurse in Wenatchee, Washington. Skiing with them was Bruno Bachinger, 40, an avid road biker and triathlete from Snohomish, Washington. Allen Ponio, 36, Ray Pinney, 32, and Shane Coulter, 30, had come down from Seattle. Coulter's wife was supposed to be there, too, but had broken her toe the day before and had to bail.

The lead guide, 30-year-old Chris “Sunshine” Edwards-Hill, was on his sixth full season in the Wallowas. Jake Merrill, a keen, lovable young “goofball” (as friend and former employer Chris Gerston of Backcountry Essentials put it) from Bellingham, Washington, was the tail guide. Merrill had a solid resume in the outdoors—especially for a 23-year-old. He’d grown up skiing and climbing on Mount Baker. He’d completed his Wilderness First Responder, Single-Pitch Climbing Instructor, and AIARE Levels 1 and 2—in addition to a number of guiding internships. This was his first trip as a full-fledged assistant guide, but everyone agreed he was more than ready. Ultimately, there's only one way to gain real experience as a guide, and that's by working as a guide.

Edwards-Hill was keenly aware of the terrain. He pointed out the deep gully that fell off to skier’s left. It wasn't easy to make out in the blowing snow. He stressed that everyone needed to stay to the right, away from the gully, and follow his tracks toward an open glade of gnarled whitebark a few hundred yards below. He reiterated protocol: Wait five to 10 turns before jumping in. There were varying accounts afterward; some recalled that he’d said five to 10 seconds. Go slow enough that you can stop above me if I stop. Follow my tracks.

Edwards-Hill made a ski-cut traverse to the right, heading across the convexity below the ridge before carving a series of turns toward the trees. The first client, Ponio, angled closer to the fall line—“along the edge of the no-go zone,” as the report would later put it. Merrill reminded the next skier—Dowling—to stay to the right, to follow Edwards-Hill’s tracks. One after the other, Dowling and then his mom and then Bachinger farmed successive lines tight and to the left of Edwards-Hill’s. Then it was Pinney’s turn. Pinney was on a splitboard. Stay to the right, Merrill said once again. Heeding the reminder, Pinney traversed farther out across the slope, beyond Edwards-Hill's initial cut, and grabbed the line to the right.

Coulter and Merrill were the last to drop in. We will never know which lines they took. In a clearing at the bottom of the run, as Dowling stopped next to Edwards-Hill below the rest of the group, a voice crackled briefly over the radio to say that a slab had broken. It was Merrill. Then the radio went silent.

—David Page

To read the rest of The Human Factor: Chapter 1, visit http://www.powder.com/human-factor/#

Photograph: Adam Clark