HOW TO CHOOSE BACKCOUNTRY SKIS

Pick the best planks for your terrain of choice.

Add 100 EUR more to quality for free Shipping!

€0,00 EUR

We often get folks emailing us here at BD asking technical gear related questions, and we do our best to respond to every single one. People are often curious about an anchor setup, product use, old gear they have and whether it’s still usable, and everything in between. They’ll also ask if we can do some testing for them. Unfortunately we can’t test everyone’s old gear found in their basement, but once in a while the QA crew will break a few things to try and comfort those climbers, while also attempting to shed light on these common gear questions.

In this QC Lab, we’ll look at four different customer product questions:

Disclaimer: As always, this is not intended to be definitive. Instead, this is some quick and dirty testing and data to help shed light on the questions and make people think. We’re basically using one data point of the suspect product, and one data point of a new comparative product. So there really is no need to inundate BD with emails and comments about the fact that this is incomprehensive and not statistically relevant—because we’re aware.

Note: For reference, some folks like thinking in Kilonewtons, some like pounds – so we reference both. 1kN = 224.8 lbf.

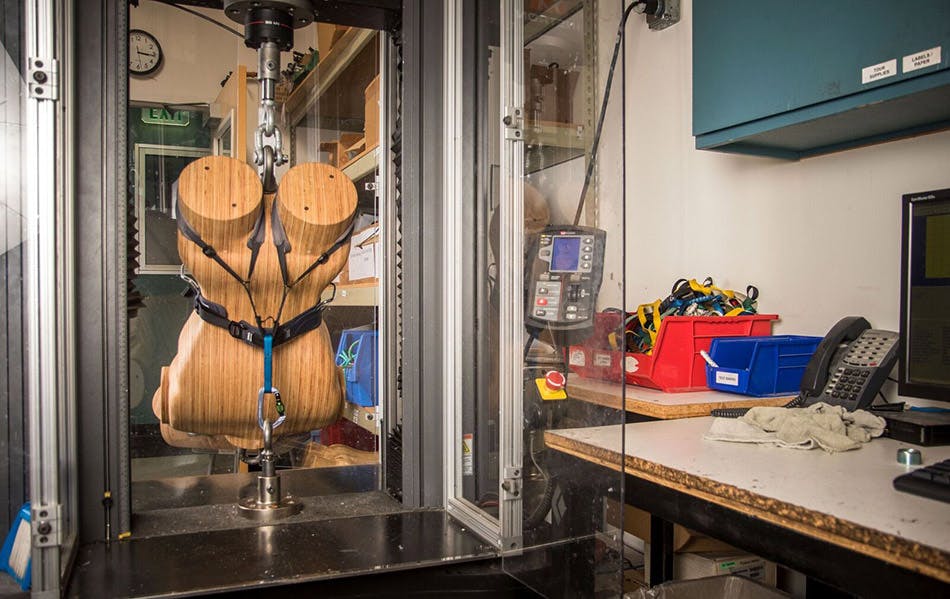

A retail store put a brand new Black Diamond Momentum harness in their display window. After several months, they were swapping out their product and noticed that the red harness had faded. They were wondering if they should discount the harness but still sell it, or throw it away. Does the sun fading the outside of the harness affect the strength and/or performance?

We tested the suspect harness, and compared it to the test results of a brand new, non sun-faded harness of the same model.

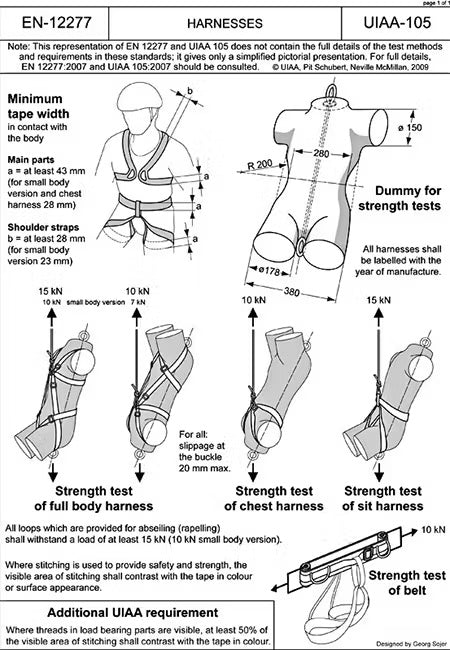

We performed the standard CE/UIAA tests, which can be found here:http://theuiaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/UIAA-105-Harnesses_May-2014.doc2_.pdf

Observations, Thoughts and Comments

With only one data point on each test, it’s not really relevant to say one is stronger than the other. However, the sun-faded harness passed the proof test and all component tests. The reality is that all values shown are basically within the range of what we would see for a new harness. That’s not to say that sun fading can’t affect strength. It most certainly can as can be seen in some previous QC lab articles. What’s important here is to realize that the construction of the harness can make a difference. This particular harness has structural webbing that is covered by a comfortable padded shell. The most visibly faded part of the harness was the padded shell (the red part), which actually doesn’t provide any strength.

If this were a different harness, or perhaps rotated in a different orientation so more of the structural webbing (waist belt for example) was exposed to the sun, then it is possible that we could see a reduction in ultimate strength.

So, though in this case, the sun didn’t appear to really affect the strength of the harness, make no doubt that sun can definitely fade structural webbing to a point where you see a reduction in strength. If your life-dependent gear is getting sun-faded, it’s usually best to be conservative and retire and replace.

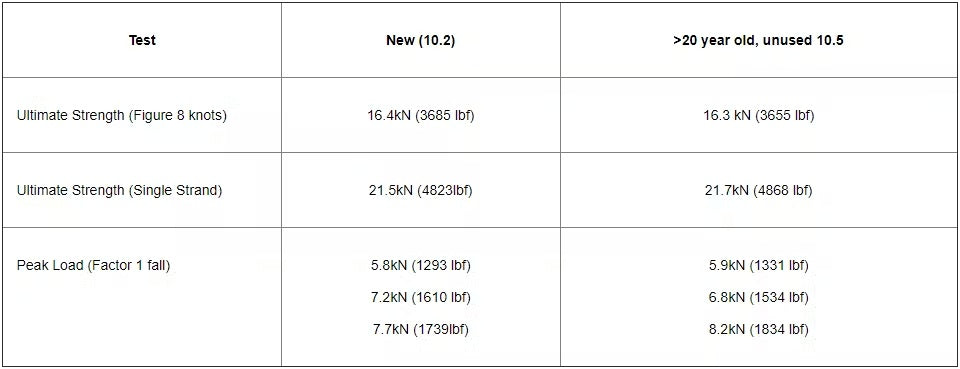

A gentleman emailed me a while ago after finding a ‘brand new OLD’ rope in his basement. It had been stored correctly (cool, dry place). It had never been used and he asked if it would behave like a new one.

Several years ago, a longtime BD employee had the same question. He had a brand new 20-year-old rope—so he brought it in and we tested it. At that time we compared it to a similar diameter rope in ultimate strength, and found that it basically was as if it was new. We decided to do the same with this rope.

We measured the diameter to be a solid old-school 10.5mm and had to do some digging to find something brand new around the office of a similar diameter. I actually couldn’t find anything in the beefcake 10.5mm, but did track down our next-year’s new Black Diamond 10.2mm cord. This time we did three very quick and dirty tests:

*It’s worth noting that though we have a drop tower in-house, we don’t currently perform the UIAA certified drops here in SLC. We typically have those performed at our rope factories.

Results

Observations, Thoughts and Comments

Once again, with pretty much only one data point in each test, it would appear that the 20-year-old new rope performs pretty much as if it was made yesterday. These were the same results I had a few years ago when testing an old, but unused rope that had been stored properly.

The old, unused rope pretty much mirrored the results of the new rope:

It’s actually unbelievable how close the results were—but we do need to remember that we’re talking about only one data point, and we’re not comparing exact samples here—the old rope is 10.5mm, and the new one is 10.2mm from a different manufacturer with likely different construction. It’s important to think of this information as directional—to give some insight.

I was doing some digging on the internet about the behavior of old, but unused ropes and found this from the Tendon website:

In the process of rope production, the fibres are mechanically doubled, twisted and braided in several stages. In this way the fibres finally attain a condition of mechanically induced stress. A long-term storage leads to retardation and relaxation. This means that stress in macromolecules is “relieving”. This phenomenon is not harmful, on the contrary it is connected with an improvement of dynamic properties. Research works showed that the results of tests of dynamic performance of ropes that had been (optimally) stored for several years were often better than values measured immediately after production. Polyamide also does not contain additives and softeners like, for example, PVC that could diffuse out. This is the reason why no embrittlement occurs.

So should you go climbing on an old, but un-used piece of gear? Well, ultimately it’s up to you. Chances are technology has changed and there is better gear on the market. In this case, this rope is considered super fat by modern standards and most folks wouldn’t be psyched to carry a big old cord like that to the crag, much less have a belay device that worked properly with it. Plus, as we all know, climbing is a serious game, so if you’re ever in doubt about your rope, or any piece of gear—it’s probably best to retire it.

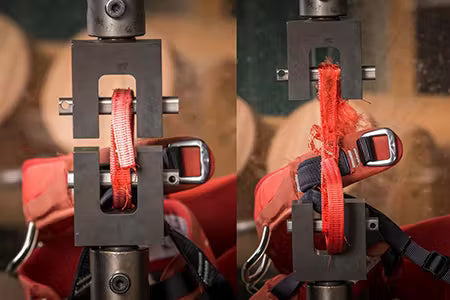

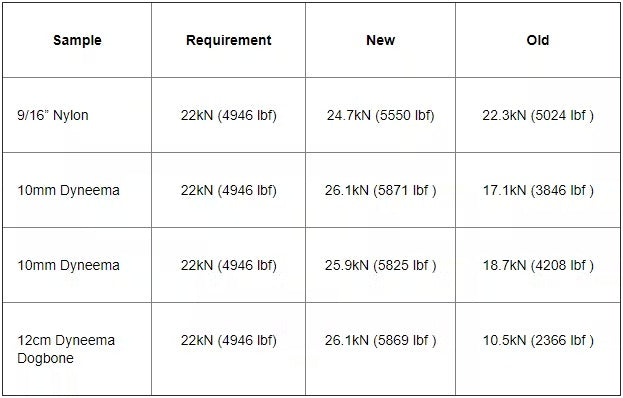

My buddy’s rack is embarrassing. I went out to climb the Diamond with him several years ago and couldn’t believe the cobbled together mess that he called a rack. Over the years since then he’s slowly built it up to be something reasonable. However, the last time we climbed together he pulled it out and now was starting to get sketched out by the state of his slings. I replaced his slings with new ones and told him we’d test them so that he can see if his fears were valid.

Observations, Thoughts and Comments

In general, though Jon Webb’s gear looked a bit beat, in MOST cases it was still actually quite strong. No, the slings didn’t always meet the requirement of 22kN, but they weren’t really near the point where it would become a safety concern under normal use.

EXCEPT …

For his EXTREMELY old and faded Dyneema Dogbone from the mid-90s. To be fair, Jon wasn’t actually climbing on this one—it was just in his pack. But it’s worth a closer look. A new sewn sling must meet 22kN, and our one new data point was over 26kN (pretty typical). Jon’s old dyneema sling checked in at 10.5kN. Now that’s getting sketchy! It’s lost over half it’s strength—from being faded by the sun, abrasion, use and age. Measuring 10kN IS a load that you could see in the field—so this qualifies as a sketchy piece of gear that shouldn’t be used—and as I said, wasn’t being used.

So other than that one, fairly obvious, old dogbone—the reality of his particular gear is that it LOOKED a bit worn, frayed and beat, though, in this case it tested to be plenty strong for typical use. Once again, the psychological affect is important. When you’re talking about life-critical equipment, it’s best to not have uncertainties lingering in the back of your mind—that way you can focus on the climbing. When in doubt, throw it out.

The real issue in this case is why was this old sketchy dogbone in Jon Webb’s pack at all? A good lesson here is IF you’re going to retire an old piece of gear, it’s best to fully destroy it so it can’t get mistaken for a functional piece and inadvertently be used in the field.

Here is an email exchange between a climber & BD customer and myself...

Customer:

I am a big BD fan and longtime user of all types of BD gear.

I enjoyed the Enormo Podcast that you did and thought of you when this situation came up.

I was on a climbing course last week and the instructor had 12 students rap off of a tree anchor. I got put on a pre-rigged 4 person Rap that had the potential for everyone to load the rope/anchor if someone lost their footing and yanked everyone else.

I was not keen on the tat and being hard into the rope with 3 other people. We had a discussion where I felt my concern was dismissed. I went back today, replaced the anchor with new cord, and cut the old cord off. One piece of 6mm cord and a ½” sling that had the date 12/14 written on it.

Is there any way I can send this to you to do a strength test? It would be great and a potential learning experience for all involved.

Thanks for the consideration.

KP:

sure

send it over

please include a copy of this email

note: on one hand gear is burly

on the other hand, gear doesn’t last forever

under normal loading scenarios - I wouldn’t be worried about that sling - loads when rapelling are quite small

but you’re right - shock loading is a different story

though nylon does absorb some energy…

my guess is though, that you guys all would have been fine

in a static test - i’m going to throw a dart and say the sling goes at >14kN

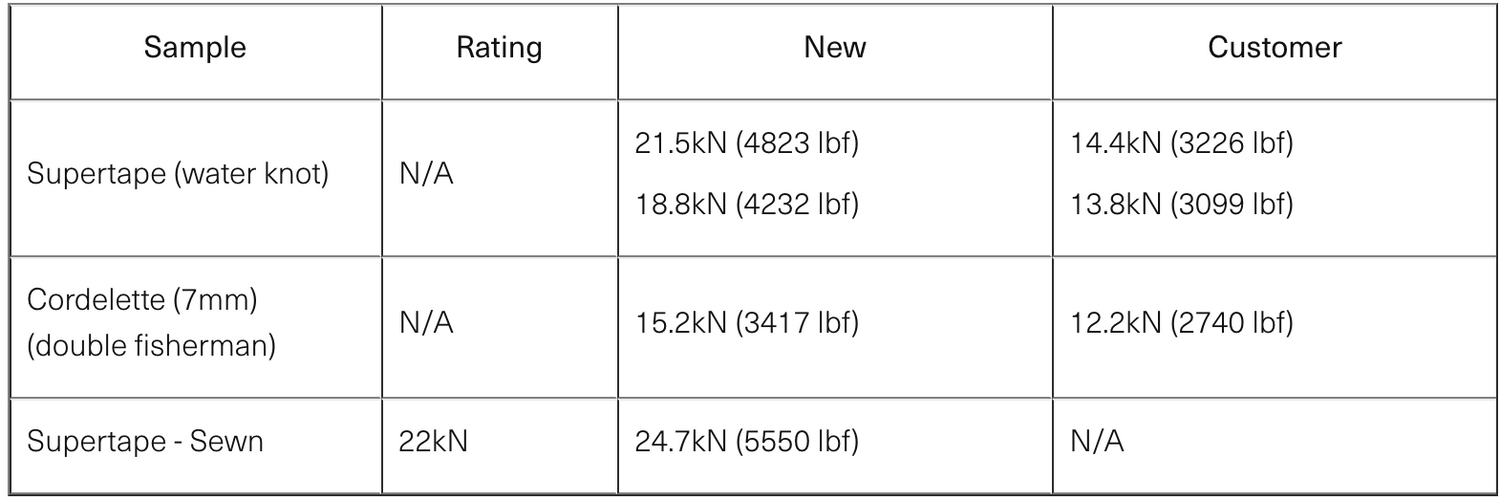

Results:

KP:

we tested using standard 10mm pins

I tied the cord in a double fisherman’s

and the webbing, I cut it in half and tied using a water knot

the cord

- broke at pin

- 12.2kN (2740lb)

the 9/16” Supertape

- sample 1 - broke at pin - 14.4kN (3226lb)

- sample #2 - broke at pin - 13.8kN (3099lb)

Looks like my guess of 14kN from my original email wasn’t too far off

so static loading with the members of your team all clipped in - no real problem

even dynamic loading - would be tough to get to those loads - especially given the fact that the materials stretch and absorb energy under dynamic loading

regardless

good on ya for replacing old tat.

hope that helps

KP

Since my response we tested a few more new pieces for comparison sake:

Observations, Thoughts and Comments

From the customer:

Thanks so much to you and to BD! Shows your commitment to safety and to the end users.

Nothing like empirical data to make good decisions!

I am surprised how strong the old 9/16” webbing was.

My perceived risk vs the real risk just got re-set.

Once again—we are looking at one data point of the customer’s slings and cordelette versus what they could do when new, and then even comparing sewn slings to knotted slings. Yes, there was a decrease in strength, but as I mentioned in my emails to the customer, in NORMAL circumstances, an anchor used for rappelling shouldn’t see loads nearly that high. Typical rappelling loads are only two or three times body weight, when bouncing down a rappel. Of course this depends on the rope (static vs dynamic), size of load, etc … but GENERALLY speaking, the rappelling loads don’t get into the double digit kN realm.

Hats off to this gentleman who took it upon himself to go back the next day and replace the slings on that rap! It’s always a good idea to carry a knife and some cord so that you can replace suspect slings in the mountains. In the grand scheme of things, it’s incredibly cheap and only takes a few minutes.

So four different user questions and four quick and dirty experiments which hopefully help shed some light:

A sun faded harness from a display window at a retail store. Does the sun affect the strength of a harness?

In this case not really, but it could, depending on the construction of the harness, orientation to the sun and how much UV it was exposed to. There is no doubt that sun-exposed webbing becomes weaker with time.

An un-used properly stored rope that is over 20 years old. Can I still climb on this cord, or should I pony up and buy a new one?

In our limited testing, this rope performed as if it was manufactured yesterday, but if it was me, I’d opt for a new higher tech cord that didn’t have me wondering about its integrity or longevity in the back of my mind.

Some slings that my buddy had on his rack and thought were looking a bit sketchy. Just because they’re ratty, should I continue using them or get some replacements?

Most of these slings were ok, and could have been climbed on longer, however, one was definitely in the sketchy zone. It’s good to remember that it’s not always easy to tell how beat or worn something is, and once again, if life-dependent gear visually looks suspect, it will affect your mind when you’re climbing, and it may be best just to replace it. And if you’re going to retire a piece of gear, best to ensure that it’s fully destroyed and thrown away so it can’t get confused with your good, usable gear.

Some webbing and cordelette that a climber was anchored to at a belay that kind of freaked him out. Four climbers at a tree belay clipped to some webbing and cordelette. Any reason for concern?

The fact that the webbing was dated (outside of the loading zone) was great and could give you a reference for how long it had been out, which was just over two years. It tested slightly weaker than if it was new, but still plenty strong for the intended application of rappelling. With years of sun exposure, this webbing would undoubtedly weaken with time, so it’s always good to be aware, inspect fixed gear, and replace if in doubt.

It’s not always easy to ascertain the structural integrity of something: you likely don’t know the detailed past – was it stored properly? How long was this webbing fixed on this route? How much sun and/or abrasion did it see?

The reality is, though gear is burly, and if taken care of appropriately it’ll last a long time, we can’t forget that it won’t last forever.

Be safe out there,

KP

Inspired by climbing, created by hand, our Spring 2026 prints tell a deeper story.

Basic field maintenance and repair tips for your climbing skins from our Reroute team.

Watch Connor take down another classic testpiece on the Empath cliff in Kirkwood, California.

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home...

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home mountains with close friends.

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard...

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard couloirs, and deep adventures in the mountains.

Watch BD Athlete Alex Honnold throw down on some hard trad high above Tahoe.