HOW TO CHOOSE BACKCOUNTRY SKIS

Pick the best planks for your terrain of choice.

Add 100 EUR more to quality for free Shipping!

€0,00 EUR

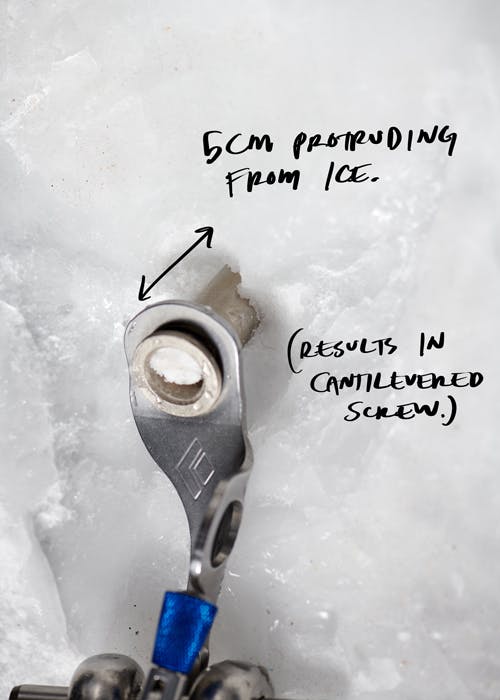

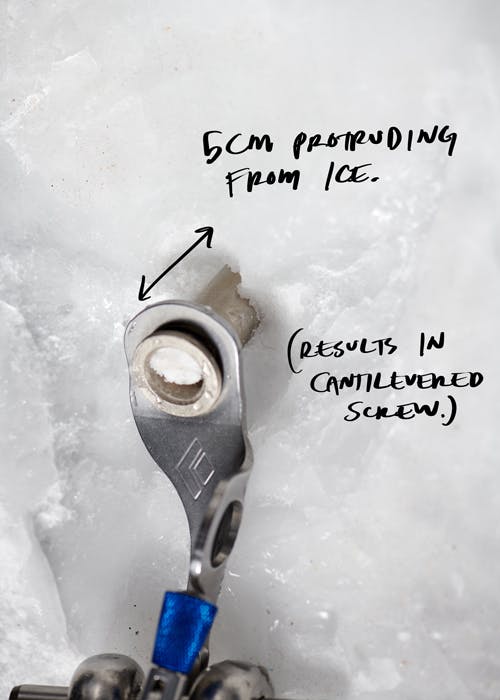

If you have been leading ice long enough you’ve most likely had a screw hit rock before the hanger was flush with the ice. Not only are you bummed because you likely just damaged the razor-sharp teeth of your screw; you now have some options to weigh. What if you don’t have a shorter screw? What if there’s no thicker ice nearby? You have some options – down climb to thicker ice, continue climbing up to thicker ice, or, as a last resort place the screw you have and tie it off or clip the hanger. Before we get into which option is best, we first need to understand how ice screw placements fail.

Ice screws themselves are very strong, but they rely on the support of the surrounding ice which can be highly variable. In a textbook placement, with the hanger flush to the ice, an applied load will stress the ice surrounding the screw and eventually cause the ice to fail and fracture in the shape of a cone around the last 3-5 centimeters of the screw nearest to the hanger. Once this occurs, the exposed section of the screw body becomes cantilevered and no longer supported by ice. The now cantilevered screw body, unable to support the load alone, will begin to bend until the hanger is levered off the head, the screw body fails, or the screw pulls out of the ice.

When the ice screw isn’t buried flush to the hanger, now forever known asscrewtrusion, the strength of the placement is compromised before a load is even applied due to the cantilevered screw body. With the increased leverage, any load applied at the hanger will have a multiplier effect on the stresses generated in the ice which will cause failure at lower loads. Therefore, it is important to always bury a screw flush with the hanger. However, if that is not an option, some questions remain. Does tying off a screw reduce leverage sufficiently to make this a better option than clipping the hanger? Is there any difference between using an aluminum or steel ice screw?

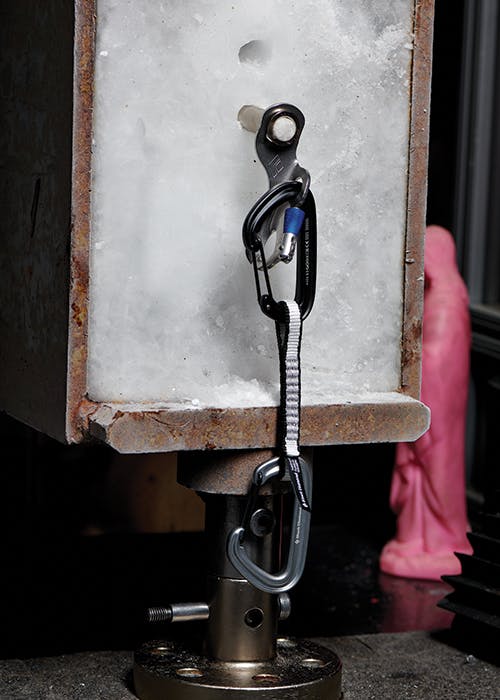

To answer this question, we headed into the QA lab to do a few quick tests and evaluate the tied-off vs clipped strength for both the BD Express (steel) and the BD Ultralight (aluminum) ice screws when placed in ice with screwtrusion. This data must be taken with a grain of salt because we’re talking about a very limited data set which is not statistically significant. It is also important to keep in mind that this testing was conducted in laboratory ice, which is solid, homogenous, and doesn’t have the same inconsistencies that are often found in the wild.

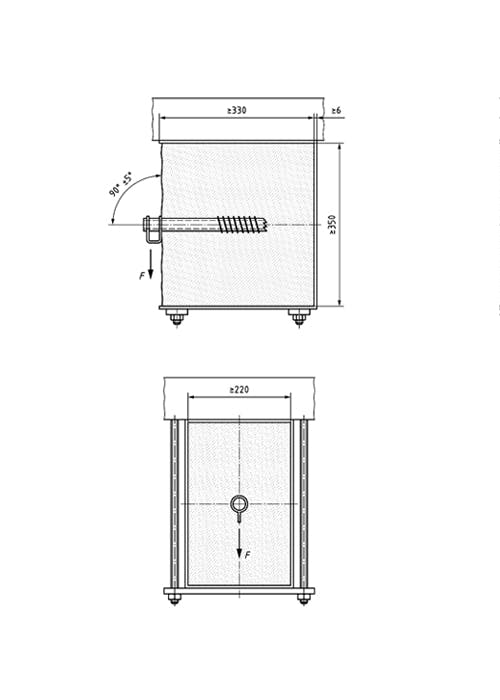

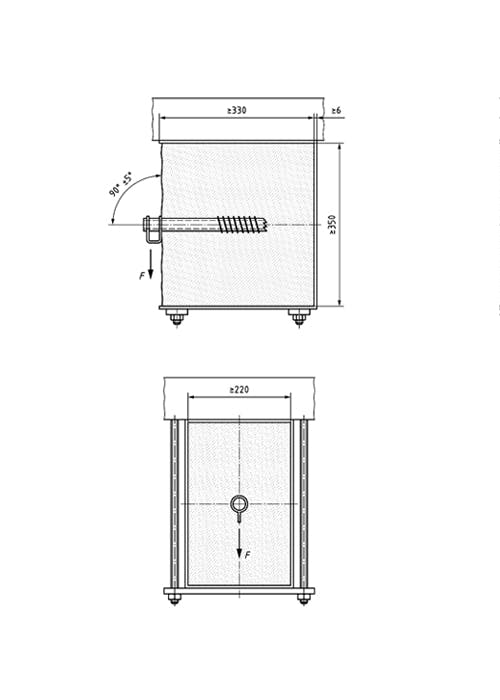

First, let’s examine the strength of both aluminum and steel screws when placed flushed to the ice, and then when placed with 5cm of screwtrusion. Three samples of both the 16cm aluminum and 16cm steel screws were tested in each configuration. For the sake of consistency, all test samples were placed perpendicular to the ice surface (at 0 degrees) per the EN568 standard test method.

Both aluminum and steel screws are rated to 10kN when fully seated in the ice as required by EN568 Mountaineering Equipment - Ice Anchors. We can see from the above data that the strength of both the aluminum and steel ice screws is significantly reduced by 5cm ofscrewtrusion. (58.7% in the case of aluminum screws and 46.4% in the case of steel screws)

Using the passive and active rock protection guidelines as reference, the minimum holding force to be safely used as a running belay is 7kN (refer to Annex A of EN12276). The steel BD Express screws result in peak loads consistently above the 7kN mark with 5cm of screwtrusion. Given the above running belay guidelines, you’re probably ok with steel screws protruding slightly. However, this is not the case for the aluminum ultralight ice screws. Further testing and regression analysis reveals that the aluminum Ultralight ice screws will provide this holding force only when protruding 3.5cm or less from the surface of the ice.

It is worth noting that although achieving loads in the field upwards of 7kN is possible, it is not common. It should go without saying that the old school mantra for ice climbing still stands – the leader shalt not fall. Falling with lots of sharp things attached to your body is a recipe for injury…

The goal of a screw tie off is to reduce the leverage on the screw body and to reduce the stresses within the ice immediately surrounding the placement. The data above, tested once again with screws perpendicular to the ice, shows that both the tied-off steel and aluminum screws result in values greater than the previously mentioned 7kN minimum for a running belay - when tested in lab ice. A major concern is that it is difficult to prevent the sling from sliding towards the hanger during a fall. As the sling slides towards the hanger, it will increase the leverage on the unsupported screw body, potentially cause a shock load, and can even get cut by the threads or the hanger.

As we all know, it is best practice to place screws at a positive angle (teeth up). However, tying off a screw is a special case that requires the screw to be placed perpendicular to the ice or at a negative angle (teeth down). Placing the screw between 0 and 15 degrees in the negative direction will help keep the sling tight to the ice surface and result in the highest holding force. Most falls also generate an outward force on the sling which can pull the sling towards the hanger even in a perfect tie off.

In ideal lab conditions, tie offs are certainly stronger than clipped hangers when protruding 5cm from the ice. However, due to the many variables influencing the strength of a tie off it is best avoided. If you do not have a shorter screw and are forced to do a tie off, then ensure that the screw is placed perpendicularly or at a negative angle, even if that means you must pull the screw and replace it in the ice. It is crucial that at least 10cm of the threads are placed in good quality ice. Clear any suspect surface ice and use a steel screw for increased strength. Finally, use extreme care to ensure the sling stays tight to the ice. A shorter screw buried to the hilt is always stronger than long screw tied off.

There has been a lot of discussion over the years surrounding placement angles. It is generally understood that the strongest placements are between 10 and 15 degrees in the positive direction (teeth upward). The ice surrounding the screw is the weak link in the system, so the goal is to place the screw in a way that reduces the stress on the ice. An upward-placed screw reduces the compressive stresses in the surrounding ice and better aligns the threads on the screw body with the fall direction—both of which increase holding power. As the screw moves towards negative placement angles (teeth downward) the holding power of the threads decreases and the stresses in the ice increase due to the levering action of the screw.

As described above, screws placed at a negative angle will lever over the ice and cause the ice to shear and cone out at much lower loads than positively placed screws. Once this occurs you are left with a protruding and unsupported screw body which leads to significantly reduced holding strength.

All of this is true for homogenous, solid ice. However, other factors like poor ice quality, variable layered ice (onion skin), temperature, air pockets, and other defects commonly found in waterfall ice will weaken the ice supporting the placement. This will cause the ice surrounding the placement to cone out or otherwise fail at much lower loads and lead to screwtrusion. Placing a screw in this type of ice is almost pointless. When placing ice screws, it is important to clear away any compromised top layers and ensure that the entire screw body is seated in solid ice. If you are forced to place a screw into marginal ice then it is safer to use a steel screw which can handle higher peak loads in the event of screwtrusion.

NOTE: The following only applies to 16cm or longer screws which are placed in at least 10cm of good quality ice. Screws less than 16cm in length do not have enough thread engagement to support the screw once the ice cones out.

Be safe out there.

Berry

Inspired by climbing, created by hand, our Spring 2026 prints tell a deeper story.

Basic field maintenance and repair tips for your climbing skins from our Reroute team.

Watch Connor take down another classic testpiece on the Empath cliff in Kirkwood, California.

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home...

Follow BD Athlete Yannick Glatthard deep into the Swiss Alps as he shares his home mountains with close friends.

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard...

Follow Dorian Densmore and Mya Akins for another winter season of steep Alaskan spines, backyard couloirs, and deep adventures in the mountains.

Watch BD Athlete Alex Honnold throw down on some hard trad high above Tahoe.