SO FINDEST DU DIE RICHTIGEN BACKCOUNTRY-SKI

Wähle die besten Bretter für dein Lieblingsgelände aus.

Du hast schon ein Konto?

Melde dich an, um schneller auszuchecken.

Add 100 EUR more to quality for free Shipping!

€0,00 EUR

MITTWOCH, DEZEMBER 20, 2023

Aluminum is Lighter than Steel

When aluminum ice screws first came onto the scene, the attraction of a lighter weight rack caused many climbers to fully switch over. The weight savings spread across a full rack of 14 screws can be upwards of 800 grams. That is serious weight, especially when it’s hanging off your harness on a steep and technical lead, or on your back for a five-hour approach.

Ultimately this means you could bring more food, more gear, or that huge belay parka, all of which may lead to more success and less suffering. But, other than weight, what are the other performance differences between aluminum and steel ice screws?

Both aluminum and steel ice screws, 13cm or longer, are CE certified and meet the EN 568:2015 10kN (2248 lbf) radial strength requirement. Although the stubby 10cm steel ice screws are not CE certified, they also meet the 10kN radial strength requirement. To put this in perspective, let’s imagine your friend Ken weighs 225lbs when loaded up with all his kit. A well-placed ice screw is rated to hold 10 Kens. It is hard to generate that much force in most real-world climbing scenarios.

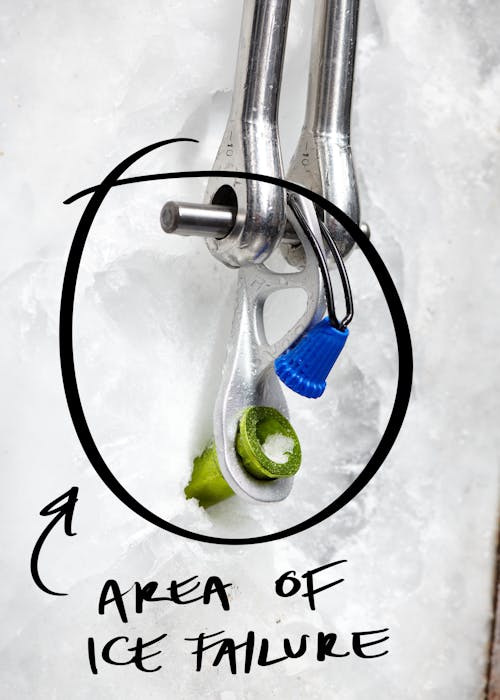

Ice screws themselves are very strong, but they rely on the support of the surrounding ice which can be highly variable, especially at the surface. In a textbook placement, with the screw placed at a slightly positive angle (tip higher than the hanger) and the hanger flush to the ice, an applied load will stress the ice surrounding the screw and eventually cause the ice to fail. The surface ice will fracture roughly 3 – 5 centimeters deep surrounding the body of the screw. Once this occurs, the exposed section of the screw body becomes cantilevered and is no longer supported by ice. The now cantilevered screw body, unable to support the load alone, will begin to bend until the hanger is levered off the head, the screw body fails, or the screw pulls out of the ice.

Da die Eisschraube nur so stark ist wie das Eis drumherum, kann es sein, dass du eine Schraube in weniger perfektes Eis setzt und das Eis bei viel geringeren Lasten zusammenbricht und sich kegelförmig abnutzt – was zu einem ungesicherten und freitragenden Schraubenkörper führt. Genau hier machen Material und Geometrie einen großen Unterschied.

Ohne zu sehr ins Detail zu gehen: Stahl hat eine höhere Duktilität und Zähigkeit als das wärmebehandelte Aluminium, das für Eisschrauben verwendet wird. Das bedeutet im Grunde, dass die Stahlschrauben mehr biegen und sich verformen können als Aluminiumschrauben, bevor sie versagen.

Design-Prioritäten

Das erzählt aber nicht die ganze Geschichte. Geometrie und Design-Prioritäten spielen in dieser Diskussion eine riesige Rolle. Als Black Diamond vor vielen Monden die steel Express ice screw entwickelt hat, stand im Vordergrund, ein robustes und langlebiges Arbeitstier zu schaffen. Dagegen wurden die aluminium BD Ultralight (UL) ice screws genau dazu – ultraleicht – konzipiert. Beide Ice Screw Designs erfüllen natürlich die 10kN-Stärkeanforderungen, aber die Design-Prioritäten sind unterschiedlich – sprich, das richtige Werkzeug für den Job.

Ein offensichtliches Beispiel für die Unterschiede in der Geometrie ist der Durchmesser der Schraubenkörper. Da Aluminium ein schwächeres Material ist, ist der Durchmesser der UL Ice Screw größer, um die erforderliche Festigkeit zu gewährleisten, die nötig ist, um die CE-Anforderungen zu erfüllen. Der größere Durchmesser kann von Vorteil sein, wenn du ihn platzierstnachgebohrte SchraubenEs kann auch das Ausrichten der Löcher erleichtern, wenn du nackte Gewinde bohrst, und die Löcher mit größerem Durchmesser verringern die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass sich das Seil verhakt, wenn du daran ziehst.

Evaluating Ice

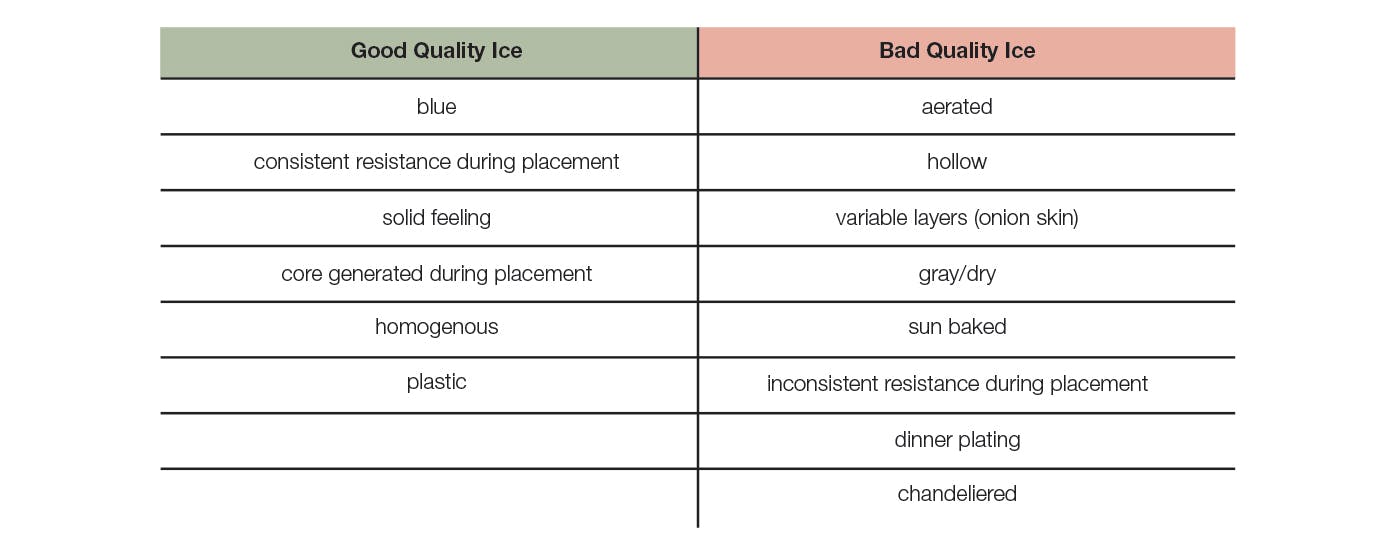

First, search for that nice homogenous, blue, plastic ice. Then, when placing the screw, pay attention to how much torque is required to turn the screw. You will generally feel consistent resistance during a placement in good ice. If you feel any significant reduction in the torque required to drill the screw, you may have hit a weak layer or an air pocket. If it’s taking a little force to turn the screw and that force is consistent all the way until the hanger meets the carefully cleaned surface ice, then we likely have a very good screw. Good screw placements also generally produce a core during placement.

Ice Quality

If the surface has been hit with sun, heat, or has lost density through sublimation (big word for what happened to your ugly white ice cubes in the freezer after a few months) then it is a lot weaker and will fracture more easily which increases the likelihood of relying on a cantilevered screw body. So, make sure to clean any weak surface ice off before placing your ice screw!

Ice Thickness

Gauge the thickness of the ice. You want to be able to bury the screw to the hanger into good ice without the threads banging into the rock and damaging your screw. And of course, ideally you don’t want the screw protruding from the ice (see screwtusion).

Wet Ice or Very Cold Ice

Aluminum screws tend to bind more on very cold days, or in ice with layers of different temperatures (really wet ice).

At the end of the day, when faced with the situation of placing an ice screw in sub-optimal ice conditions you should search elsewhere to find a better placement. You may have more buffer with a steel ice screw but relying on ice screws in marginal ice is not a good strategy. Taking the time to get good screw placements is very important! The best option, whether you are using steel or aluminum, is to get down to that nice blue plastic ice we all love to see.

Reale WeltAls Kletterer liegt es in unserer Verantwortung, die besten Werkzeuge für den Job auszuwählen und die Grenzen unserer Ausrüstung zu kennen.

Viele Leute hier bei BD, mich eingeschlossen, und auch Athleten wie Will Gadd, verwenden je nach Einsatzzweck eine Mischung aus Aluminium- und Stahl-Eisbohrschrauben. So kannst du die Vorteile beider Modelle voll ausnutzen. Neu bohren? Dann greif zur Aluminium-Eisbohrschraube mit dem größeren Außendurchmesser. Gewinde bohren mit deiner 23cm-Schraube? Dann nimm die Aluminiumschraube, um die Löcher leichter auszurichten und Gewicht zu sparen. Auf zu einem Gletscherwander? Dann schnapp dir die Aluminiumschrauben und spar etwas Gewicht. Auf zu einer abgelegenen Mission im Backcountry, wo Gewicht das A und O ist? Dann setz voll auf Aluminium.

Hast du es mit fragwürdigem Eis zu tun? Schnapp dir die Stahlschraube, um deine Sicherheitsmargen zu erhöhen – oder besser noch, frag dich, ob es sich überhaupt lohnt, die Route zu klettern. Zu wissen, wann du besser zurücktrittst, statt das Risiko einzugehen, bei einem Sturz auf unsicherer Ausrüstung zu landen, ist entscheidend, um in den Bergen sicher zu bleiben.

Wähle die besten Bretter für dein Lieblingsgelände aus.

Von der Kletterwelt inspiriert, von Hand gefertigt – unsere Prints für Frühjahr 2026 erzählen ihre...

Von der Kletterwelt inspiriert, von Hand gefertigt – unsere Prints für Frühjahr 2026 erzählen ihre ganz eigene Geschichte.

Einfache Tipps zur Pflege und Reparatur deiner Steigfelle vom Reroute-Team.

Schau zu, wie Connor am Empath-Felsen in Kirkwood, Kalifornien, ein weiteres legendäres Testpiece abräumt.

Stell dir dein perfektes Outdoor-Outfit zusammen – egal ob strahlender Sonnenschein oder Schneesturm.

Black Diamond Athletin Angela Hawse ist eine Wegbereiterin für Veränderung.

Das brauchst du für jede Art von Skitouren-Abenteuer.

Stell dein Setup für die nächste Skitour perfekt ein.

Begleite BD-Athlet Yannick Glatthard tief in die Schweizer Alpen, während er seine Heimatberge mit guten...

Begleite BD-Athlet Yannick Glatthard tief in die Schweizer Alpen, während er seine Heimatberge mit guten Freunden teilt.

Begleite Dorian Densmore und Mya Akins durch eine weitere Wintersaison voller steiler Alaska-Spines, versteckter Backyard-Couloirs...

Begleite Dorian Densmore und Mya Akins durch eine weitere Wintersaison voller steiler Alaska-Spines, versteckter Backyard-Couloirs und tiefer Abenteuer in den Bergen.

Wir bringen Licht ins Dunkel, wenn’s um Stirnlampen geht.

Schau dir an, wie BD-Athlet Alex Honnold hoch über Tahoe beim harten Trad-Klettern alles gibt.