DER BD GUIDE FÜR TECHNISCHE JACKEN

Unverzichtbarer Schutz, wenn das Wetter umschlägt – nicht deine Pläne.

Du hast schon ein Konto?

Melde dich an, um schneller auszuchecken.

Add 100 EUR more to quality for free Shipping!

€0,00 EUR

With dozens of companies making untold numbers of carabiners these days, it can be a real chore to navigate through countless different models to choose the one that's right for your type of climbing. Wiregate vs. standard gate. AutoLock vs. screwgate. Ultralight vs. heavy. What biners should I use on my slimmed-down alpine rack as opposed to my daily sport cragging kit? As with most pieces of climbing gear, there is a certain amount of inherent versatility, but often certain products are better suited, and more often than not designed specifically for certain applications. As with almost anything, it's always prudent to select the right tool for the job. This month we'll attempt to distill the basics of carabiner usage to help you figure out what's the right choice for your type of climbing.

We'll start off with a quick word on basic carabiner use because we get this question all the time.

I get lots of random calls from arborists, fire departments, rescue workers, marinas, yachting folks, Jeep guys and warehouse personnel wanting to know if it's okay to use our carabiners for their particular application. The official answer is always no, not recommended. Just as all of our instructions say, our gear is "For Climbing and Mountaineering Only." But why?

The simple answer is that we are climbers and mountaineers, we know climbing and mountaineering, and we design, test and certify our gear for climbing and mountaineering. We're not as intimate with the loads, the uses, misuses and abuses of these other applications.

What many people may not realize is the different ways that recreational gear is designed, tested and rated compared to industrial equipment. Industrial connectors are usually made of steel, are much heavier, are often much stronger, certified to different standards, and are sometimes rated differently than aluminum climbing carabiners.

Depending on what standard an industrial connector is certified to, and it’s intended application, it may be rated to either it’s Safe Working Limit (SWL) and/or it’s Minimum Breaking Strength (MBS). The steel connector on the left in the photo below has an MBS of 45kN - if it sees a load of 45kN, it will break. However, if a connector is marked with it’s SWL, it will have a safety factor included which could be anywhere from a factor of 4 and up. For example, let’s say a steel industrial connector is marked with a SWL of 10kN and is certified to an industrial standard which requires a safety factor of 4. This means that you can load the connector safely to 10kN - and that it won't actually break until a minimum of 40kN. However, climbing gear is always rated to the load at which it will actually break. So a 20kN carabiner actually breaks at that load. There's a big difference.

Bottom line: Climbing gear shouldn't be used in industrial applications—it just isn't designed, rated or certified for those types of loads and applications.

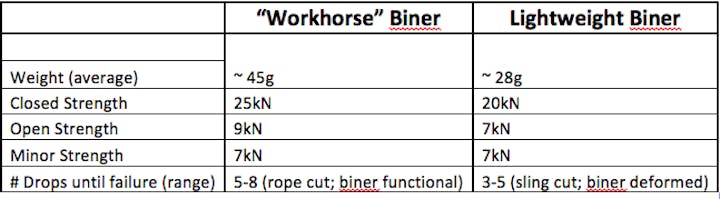

As far as carabiner "strength" is concerned, almost every carabiner available today is CE certified. This means they meet minimum strength requirements. A bunch of smart people have spent a lot of time determining what these standards should be, given real-world climbing and mountaineering loading scenarios. There are some subtle differences and exceptions when getting into the nitty gritty of different kinds of carabiners, but for argument's sake, the minimum strength requirements for most climbing carabiners are:

Closed gate strength - 20kN

Open gate - 7kN

Minor axis - 7kN

Selbst in der Welt der Kletter- und Bergsteigerausrüstung, insbesondere wenn es um Karabiner geht, fragt man sich: Welches Modell oder welcher Stil passt am besten? Black Diamond stellt allein über 30 verschiedene Arten von Karabinern her. Von reinen Sicherungs-Karabinern, Schließkarabinern, Drahttoren, Keylock- und traditionellen Tor-Karabinern bis hin zu Karabinern mit "Hoods" und mittlerweile sogar Karabinern mit Magneten. Wie sollst du wissen, welches Werkzeug für den Job das Richtige ist? Ich spreche hauptsächlich über das Karabiner-Angebot von Black Diamond, weil ich diese selbst benutze und sie am besten kenne.

Belay Karabiner

Belay-Biner, auch als HMS-Biner bekannt, sind immer verriegelt und haben typischerweise ein großes Korbende, um die Verwendung eines Munter-Hitches zu ermöglichen. Es gibt schwerere, größere Varianten, die in der Regel aus einem dickerem Stab gefertigt werden, und es gibt kleinere, oft leichtere Versionen, die meist eine ausgeprägtere I-Träger-Konstruktion aufweisen – das bringt Material dorthin, wo die nötige Festigkeit erreicht werden muss, entfernt aber überschüssiges Material von Stellen, wo es nicht benötigt wird, was zu einem leichteren Karabiner führt.

As well as the different types of locking mechanisms described above, there are two general families of lockers: big and small. Typically large lockers are used for belaying (as stated above), setting up top ropes, or acting as the power point in anchors. Smaller lockers are often used to build anchors, on a particular placement where you could be concerned about the gate opening, or to clove yourself into an anchor.

Wiregate vs Non-Wiregate

In 1995, Black Diamond brought wiregate technology to the climbing industry with the HotWire carabiner. Wiregate carabiners are typically lighter, less susceptible to freezing, and because of the reduced mass, less susceptible to gate whiplash. During a climbing fall there is a lot going on-carabiners are getting loaded, ropes are stretching and getting tight, things are bouncing around. Traditional gates on carabiners have more mass to them, and during all of this bouncing and vibration, it has been shown that the mass of the gate can allow it to open slightly which in effect results in an 'open gate' loading scenario. And as stated above, carabiners are typically 3 to 4 times as strong when the gate is closed. The reduced mass of a wiregate carbiner alleviates this.

Personally I like the fact that wiregate biners are usually lighter and less susceptible to freezing so I typically use them for long routes with long approaches, and ice or alpine climbing.

Keylock Gate vs. Non-Keylock Gate

Carabiners historically used a 'hook and pin' configuration to allow the gate to interface with the body of the biner and give it its strength during closed-gate loading. This style is consistent, strong, relatively easy to manufacture and relatively cheap.

Ein weiteres solides Tor-Design kam vor einigen Jahren ins Spiel – das Keylock-Tor. Es nutzt die Geometrie der Tasche des Tors, um mit der „Nase“ des Karabiners zu interagieren und so dessen Stärke im geschlossenen Zustand zu gewährleisten. Der Vorteil dieses Designs liegt darin, dass es die Wahrscheinlichkeit verringert, dass sich der gehakte Teil des Karabiners an etwas verhakt (wie etwa an einem Bolzenhänger, Stopper-Draht oder Sling). Carabiner, bei denen die Nase eingehakt wird, sind überraschend schwach – und das ist bei Weitem das häufigste Szenario für Ausfälle im Feld. Schau dir einen alten QC Lab-Beitrag zum Thema an.

Der Herstellungsprozess zur Herstellung von keylock gates ist etwas teurer, aber du profitierst von einem verhakungsfreien Karabiner.

Bis vor kurzem, wenn du zu den Leuten gehörtest, die das verhakungsfreie Keylock-Design richtig cool fanden, aber auch das geringere Gewicht und das Fehlen des Peitscheneffekts beim Wiregate schätzten, musstest du dich entscheiden. Aber jetzt erledigt BD's HoodWire Technology zwei Fliegen mit einer Klappe. Du bekommst die Funktionalität eines Wiregate-Karabiners und gleichzeitig die verhakungsfreien Vorteile eines Keylocks dank der einfachen Drahthaube des Karabiners. Die HoodWire Technology ist sowohl beim HoodWire-Karabiner als auch bei unserem aktualisierten Oz-Karabiner erhältlich.

Als unser Oz-Karabiner erstmal herauskam, rief mich mein Kumpel Travis total aufgeregt an: "Ich werde mir ein komplettes Set Oz-Quickdraws für mein neues Sportkletter-Set bestellen. Die sind so leicht!" Es stimmt, der Oz ist ein superleichter Karabiner mit nur einem Unze (daher auch der Name), aber ist er die richtige Wahl für deine Sportkletter-Zugängervorrichtungen? Klar, wenn du eine Mehrseillängenroute in den Canadian Rockies machst oder einen harten 22-Zugonsight angehst, dann versuch’s ruhig. Aber als Arbeitstier für deine Sportkletter-Karabiner ist er wahrscheinlich nicht die beste Wahl. Warum? Um das Gewicht aus diesen ultraleichten Karabinern zu nehmen, entfernen die Hersteller Material – und obwohl letztendlich alle Karabiner stark sind und alle CE-Anforderungen erfüllen, kann weniger Material ein paar Dinge bedeuten. Die kleinere Größe macht es etwas schwieriger zu clippen. Es kann weniger Material am Rücken geben, was ihn anfälliger für Biegungen macht, wenn er über eine Kante belastet wird, und oft gibt es weniger Material auf der seilführenden Fläche, was bedeutet, dass Whippers mehr an deinem Seil zehren.

Ein Quickdraw, der eher für den täglichen Cragging-Einsatz optimiert ist, hätte wahrscheinlich einen schnorrefreien Karabiner oben, sodass er nicht an Bolthaltern hängen bleibt, und unten einen richtig großen Karabiner, um das Einhängen zu erleichtern. So etwas wie das sportkletterspezifische Livewire Quickdraw, Nitron Quickdraw oder Hoodwire Quickdraw.

For most of the larger, heavier biners, the rope actually eventually ended up cutting, and the biner was still in good enough shape to throw on your rack and keep climbing. Whereas with the lightweight, smaller biners, after anywhere from 3-5 drops, the biner was severely deformed and was what I would consider non-functional (gate wouldn't open), and on a few occasions, the 10mm Dynex sling eventually cut.

Offensichtlich ist dieser Test brutal hart – niemand bei klarem Verstand würde (oder könnte) wiederholt gnarly Fallfaktor-1,7-Whipper mit statischer Sicherung an demselben Seilabschnitt in Kauf nehmen – aber im Vergleich dazu haben die leichten Biners schon früher das Nachsehen gehabt. What's the moral of this story? Use the right tool for the job. Schwerere Biners mit größerem Querschnitt haben ihren Platz, denn sie sind robust und können einiges einstecken. Verwende so etwas wie diese für deine täglichen Cragging Quickdraws, bei denen du eher immer wieder fällst, während du an deinem großen Proj arbeitest. Die kleineren, leichten Biners hingegen sind nicht dafür ausgelegt, denselben Strapazen standzuhalten, und eignen sich besser, wenn Gewicht eine Rolle spielt und du nicht so häufig riesige Lobbers erlebst – wie etwa in alpinen Umgebungen oder beim Eisklettern.

Wir starten mit ein paar schnellen Worten zur grundlegenden Verwendung von Karabinern, weil uns diese Frage ständig gestellt wird.

Ich bekomme viele zufällige Anrufe von Arboristen, Feuerwehren, Rettungskräften, Marinas, Yachting-Fans, Jeep-Leuten und Lagerpersonal, die wissen wollen, ob sie unsere Karabiner für ihre spezielle Anwendung benutzen dürfen. Die offizielle Antwort lautet immer: Nein, nicht empfohlen. Wie in all unseren Anweisungen steht, ist unser Equipment "For Climbing and Mountaineering Only." Aber warum?

Die einfache Antwort ist, dass wir Kletterer und Bergsteiger sind, wir kennen uns mit Klettern und Bergsteigen aus und entwerfen, testen und zertifizieren unsere Ausrüstung für das Klettern und Bergsteigen. Wir kennen uns nicht so gut mit den Lasten, den Anwendungen, Missbrauch und Fehlanwendungen in diesen anderen Bereichen aus.

Viele wissen vielleicht gar nicht, dass Freizeit-Ausrüstung ganz anders konstruiert, getestet und bewertet wird als Industrieausrüstung. Industrielle Steckverbinder bestehen meist aus Stahl, sind viel schwerer, oft viel robuster, nach anderen Standards zertifiziert und werden manchmal auch anders bewertet als Aluminium-Kletterkarabiner.

Unverzichtbarer Schutz, wenn das Wetter umschlägt – nicht deine Pläne.

NOLS-Stipendiatin Lauryn Bailey erzählt von ihren Erlebnissen mit NOLS in der Wind River Range.

Wähle die besten Bretter für dein Lieblingsgelände aus.

Von der Kletterwelt inspiriert, von Hand gefertigt – unsere Prints für Frühjahr 2026 erzählen ihre...

Von der Kletterwelt inspiriert, von Hand gefertigt – unsere Prints für Frühjahr 2026 erzählen ihre ganz eigene Geschichte.

Einfache Tipps zur Pflege und Reparatur deiner Steigfelle vom Reroute-Team.

Schau zu, wie Connor am Empath-Felsen in Kirkwood, Kalifornien, ein weiteres legendäres Testpiece abräumt.

Stell dir dein perfektes Outdoor-Outfit zusammen – egal ob strahlender Sonnenschein oder Schneesturm.

Black Diamond Athletin Angela Hawse ist eine Wegbereiterin für Veränderung.

Das brauchst du für jede Art von Skitouren-Abenteuer.

Stell dein Setup für die nächste Skitour perfekt ein.

Begleite BD-Athlet Yannick Glatthard tief in die Schweizer Alpen, während er seine Heimatberge mit guten...

Begleite BD-Athlet Yannick Glatthard tief in die Schweizer Alpen, während er seine Heimatberge mit guten Freunden teilt.

Begleite Dorian Densmore und Mya Akins durch eine weitere Wintersaison voller steiler Alaska-Spines, versteckter Backyard-Couloirs...

Begleite Dorian Densmore und Mya Akins durch eine weitere Wintersaison voller steiler Alaska-Spines, versteckter Backyard-Couloirs und tiefer Abenteuer in den Bergen.

Wir bringen Licht ins Dunkel, wenn’s um Stirnlampen geht.