SO FINDEST DU DIE RICHTIGEN BACKCOUNTRY-SKI

Wähle die besten Bretter für dein Lieblingsgelände aus.

Du hast schon ein Konto?

Melde dich an, um schneller auszuchecken.

Add 100 EUR more to quality for free Shipping!

€0,00 EUR

Die Tour, auf der wir an diesem Tag waren, war eher eine Mission, um uns die Klettermöglichkeiten in der Gegend anzuschauen, als ein Tag, an dem wir ein paar Schwünge gefahren wären. Wir sind etwa 12km (7.5 miles) die Moraine Lake Road hinaufgefahren und haben einen schnellen Snack zu uns genommen, bevor wir den Sommer-Wanderweg zu Larch Valley gestartet haben.

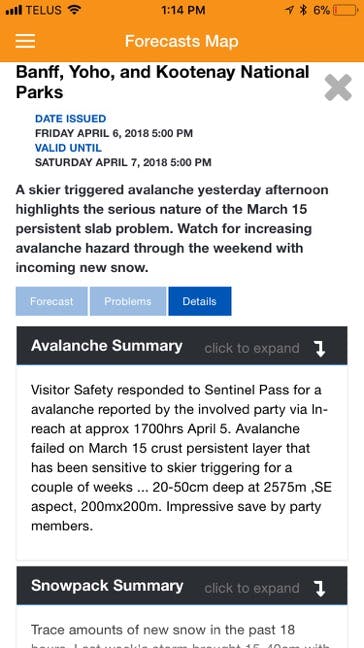

Der Larch Valley Trail bis zum Gipfel des Sentinel Pass sind zusätzliche 6,8 km (4,25 miles) mit 735 m (2425ft) Höhengewinn. Wir waren gerade kurz davor, den Passgipfel zu erreichen, als ich nach unten schaute und einen rasant auftretenden Riss an meinem Ski entdeckte. Ich dachte, das ist ein schlechtes Zeichen, vielleicht sollten wir nicht hier sein, und drehte um, um mit meinen Partnern darüber zu sprechen, ob wir umkehren sollten. Da sah ich, dass wir alle von der Lawine erfasst wurden, und mir wurde klar, dass ein großer Teil des Hanges, auf dem wir waren, gebrochen war – soweit ich damals sehen konnte, ungefähr 200-225 m (650ft-750ft) breit.

I initially tried to self-arrest, being close to the crown of the avalanche, and thought I had a chance of stopping myself or at least staying on top of the debris by slowing myself enough that the bulk of the snow would go downhill faster than me, leaving me on top.

As soon as I realized I was likely going to stop or at least be on top of the snow I started looking for my partners. The closest partner was still on top of the snow and I watched her ride the snow down almost like she was sitting in a chair. I hadn’t seen her initial struggle while also trying to self-arrest, but watched the slide carry her approximately halfway down the slope. I immediately noticed our third partner, who was around 100ft behind us, was already buried and I hoped to see some part of her re-surface so I could get a reference point while the snow was moving. Unfortunately,I didn’t see anything. I was trying to track both of them simultaneously, but I had a good idea of where the partner who was above the snow was and where she would likely end up if she did get buried. The other buried partner was more of a concern, so I paid closer attention to where I thought she was in the snow and where that mass of snow stopped. The crown spread across two aspects and the way the two slopes funneled together, along with how the slope angle changes abruptly at the bottom of the pass created a large wave that rose up like an ocean swell. It looked like she was probably underneath it. It was clear that it was a deep burial from the start, but I never expected it to be ~4m (13ft).

I wrote a more in-depth trip report about the experience in the local Canadian Rockies backcountry ski Facebook group and it was reposted by Gripped here.

Paul Clarke from the Rocky Mountain Outlook, Canmore’s newspaper, also wrote about it here.

In a quick summary, I fell from where I had self-arrested approximately 200 meters down the icy layer the avalanche slid on and ended up very close to the partner who was partially buried. We quickly checked ourselves to make sure we were ok, turned our beacons to receive and immediately headed in the direction where the wave of snow had formed. The partially buried partner was ok but still stuck in the snow buried from the legs down. However, she could get herself out so I left her and started the search.

My beacon quickly went from 35m to 20m to 12m when I heard my partner say that she had a reading closer to 9m. I immediately headed toward her and the distance on my screen started to decrease, 8m then 6m and then 4m but after that the numbers started going up again. The distance went back up to 5m and then to 6m. I backtracked, reversing back to the smallest reading and checked the other directions—the numbers all increased again, and 4m was the smallest number we saw. It seemed like she was vertically 4m below us. We were both in shock.

I had taken two AST-1 courses previously, but they were in 2004 and 2006. I don’t remember much of the details from them, but I certainly didn’t remember them covering what to do if your partner is buried deeper than the length of your probe. One thing I found, however, was the ease at which a new beacon helped me to locate the buried skier. On those avalanche courses I had taken previously I had an old analog beacon and I do remember listening to beeps and the whole process of finding a buried skier being time-consuming and not straightforward in training.

Approximately a year ago, I updated my avalanche beacon, primarily because I spend a lot of time in avalanche terrain for fun and work. It felt right to get a new beacon, as having a beacon from 2004 didn’t seem fair to either the people who cared about me or to my partners anymore. The second reason I had upgraded my beacon was because I wanted to be able to use the TX 600 which would allow me to have a secondary beacon for Trango, my dog, that I could search for on a different frequency (456hz) than traditional beacons at 457hz. I didn’t really research new beacons that much, I just knew I wanted something with three antennas and the ability to switch to a different frequency so that I could use the TX 600 transmitter as well, which limited me to the PIEPS DSP pro(redesigned as the PIEPS Pro BT).

Unsere Erinnerungen an diesen Teil der Rettung sind ein bisschen verschwommen. Es gibt Momente, in denen ich mich nicht daran erinnere, wer was gemacht hat, aber ich erinnere mich, wie ich da saß und dachte: "Verdammt, sie ist 4m begraben … wir sind am Arsch." Zum Glück hatte mein Partner eine längere Sonde, näher an 3m, aber trotzdem zeigten unsere Beacons 4m. Wir holten schnell unsere Schaufeln und Sonden, setzten sie zusammen und machten eine zackige Suchprobe. Wir hatten keinen Treffer – was wir auch nicht erwartet hatten – und fingen an herauszufinden, was als Nächstes zu tun ist.

Die 4m Messung kam nicht vom Stehen, sondern als der Beacon direkt auf den Schnee gelegt wurde, während wir versuchten, den genauen Standort des vergrabenen Skifahrers zu bestimmen. Ich habe schnell in Schaufeltiefe gegraben und den Beacon wieder auf den Schnee gesetzt, und er zeigte 3,8m an. Mir wurde beigebracht, zuerst zu testen und dann nochmal, also habe ich es wiederholt: nochmal in Schaufeltiefe gegraben und den Beacon auf den Boden gelegt, woraufhin er 3,6m anzeigte. Daraus schlossen wir, dass wir in die richtige Richtung gingen, und beschlossen zu graben.

Als ich das erste Mal Orange unter dem Schnee entdeckte, war ich wieder total schockiert. Wir hatten sie gefunden! Gleichzeitig hatte ich große Bedenken, in welchem Zustand sie sein würde. Ich war schon in anderen Situationen als Ersthelfer dabei gewesen und hatte diesen Moment mit einer engen Freundin gar nicht herbeigesehnt. Dann machte sie Geräusche. Sie lebte! Danach haben wir ihre Atemwege freigemacht und Schnee um ihren Pack entfernt, damit sie genug Platz hatte, ihre Brust auszuweiten und atmen konnte.

Wir fanden den inReach in ihrem Pack, lösten den SOS aus und gruben sie vielleicht zwei weitere Stunden lang aus diesem Loch. Beim Graben kamen wir zuerst in Kontakt mit ihr in der Nähe ihres Kopfes, aber ihr Unterkörper und ihre Skier steckten noch im Schnee fest. Sie waren noch einen Meter weiter unten und weiter von uns entfernt. Nachdem wir ihr Gesichts- und Schulterbereich frei gegraben hatten, dauerte es länger als gedacht, sie vollständig zu befreien, weil sie noch an ihren Skiern hing. Unser Hauptziel war, ihr einen freien Atemweg zu verschaffen und uns dann um alles Weitere zu kümmern. Wir wussten, dass es lange dauern würde, bis wir beide sie befreien konnten.

Es gibt definitiv ein paar Erkenntnisse für mich, die ich bei meinen zukünftigen Abenteuern in den Bergen anwenden werde.

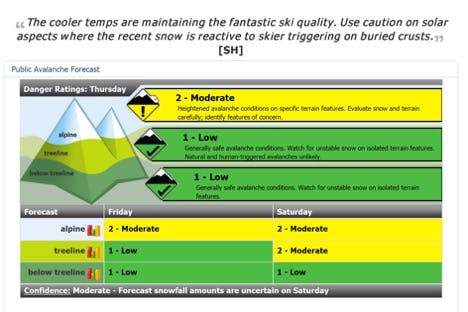

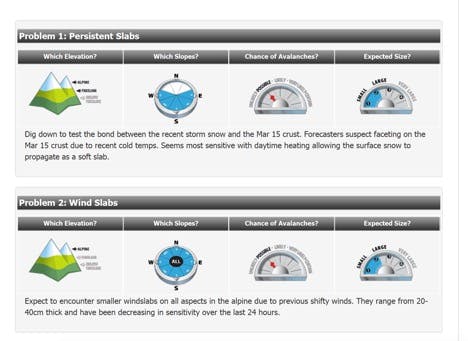

1. Lies die Wettervorhersage im Detail. Am Morgen der Lawine war ich in Eile und habe dem Bulletin nicht allzu viel Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt. Ich sah Niedrig/Niedrig/Mäßig und las nicht weiter. Wenn du die Vorhersage von diesem Tag genauer betrachtest, wird die Möglichkeit diskutiert, die Schicht auszulösen, die wir auf demselben Hang aktiviert haben, an dem wir hochgezogen sind. Ich möchte in Zukunft lieber nicht noch einmal in eine Lawine geraten.

2. Ein Verständnis dafür zu haben, wie deine Ausrüstung funktioniert und wie du sie benutzt, ist entscheidend. Zum Glück hat mein neuer Beacon genau so funktioniert, wie ich es erwartet hatte – einfach einschalten und den Pfeilen folgen – und ich kann mir kaum vorstellen, was passiert wäre, wenn er das nicht getan hätte. Ich hätte mir auch gewünscht, dass ich mit dem inReach meines Freundes vertrauter gewesen wäre. Als Technik-Fan und regelmäßiger Gadget-Nutzer dachte ich, dass die Bedienung eines inReach ganz unkompliziert wäre, aber ich war überrascht, wie kompliziert es sich unter Stress anfühlte. Es ist nicht so, ich konnte es nur nicht richtig verstehen, aber zum Glück hatte mein Partner den Kopf dafür, die Anleitung auf der Rückseite des Geräts zu lesen und den SOS auszulösen.

3. Früher habe ich offen gesagt, dass ich nie eine Sonde kaufen würde, die länger als 3 m ist, weil sowieso niemand unter 3 m leben wird. Statistisch gesehen ist das eine ziemlich wahre Aussage, wenn man bedenkt, dass die Überlebensraten bei 2 m nur 3 % betragen. Zwei Tage nach unserem Absturz habe ich eine neue 320 cm lange Sonde gekauft. Ich habe meine Lektion gelernt. Als Fotograf habe ich immer eine DSLR, ein extra Objektiv und ein oder zwei Batterien im Rucksack, aber ich habe beim Equipment, das das Leben eines Freundes retten kann, am Gewicht gespart. Beim nächsten Mal nehme ich nicht die extra Kamera-Batterie mit, sondern die längere Sonde.

4. Ich würde dasselbe über die Schaufel sagen. Ich habe eine größere Schaufel, aber ich nehme die normalerweise auf längeren Touren mit, die über Nacht gehen, wo ich Schneewände baue und viel buddeln muss, statt auf Tagestouren. An dem Tag hatte ich eine kleinere Schaufel, um Gewicht zu sparen. Ich werde die kleine Schaufel bei ähnlichen Touren so bald nicht wieder mitnehmen. Ich werde einfach ein bisschen mehr anstrengen und ein paar Gramm/Unzen mehr an Ausrüstung tragen. Irgendwann beim Buddeln haben wir kurz die Schaufeln getauscht, und da wurde mir klar, dass eine größere Schaufel bei unserem Unfall geholfen hätte.

Ein paar Lawinenverbände haben sich an mich gewandt und gefragt, was ich dafür halte, dass es wichtig sei, den Schnee an der Stelle zu beobachten, an der ich vermutete, dass der verschüttete Skifahrer liegt, solange der Schnee noch rutscht. Ich fand das entscheidend für unser Timing, sie zu finden, denn sobald wir mit der Suche begannen, blieb kaum Zeit für Blödsinn, und in den ersten ein bis zwei Minuten waren wir bereits innerhalb von 10m von ihr, weil wir ungefähr wussten, wo sie verschüttet war.

Im Jahr 2012 Studie Pascal Haegeli von der Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, hat kanadische mit schweizerischen Überlebensraten basierend auf der Verschüttungszeit verglichen. Dabei wurde gezeigt, dass in Kanada mit zunehmender Verschüttungszeit deine Chancen, eine Lawine zu überstehen, deutlich sinken. Das ist erwartbar, und das gesamte Überlebensfenster liegt eher bei 10-18 Minuten. Für mich unterstreicht das, wie wichtig es ist, schnell deinen Partner zu finden – und ich glaube, dass genau deshalb das Beobachten des Schnees und Beacons der neueren Generation so entscheidend ist.

Es gab menschliche Faktoren, die zu unserem Vorfall geführt haben, und ich denke, wenn ich die Vorhersage komplett gelesen hätte, inklusive der schriftlichen Details, hätte das vielleicht den Ablauf an diesem Tag verändert. Auf jeden Fall, wenn ich wieder Low/Low/Moderate sehe, nehme ich nicht einfach an, dass alles in Ordnung ist, sondern schaue mir das Lawinenbulletin genauer an.

Ich überlege, in Zukunft öfter ein zweites Kommunikationsgerät mitzuführen. Das mag für eine leichte und schnelle alpine Route zu viel Ausrüstung sein, aber für andere Routen sehe ich das durchaus sinnvoll. Ich denke daran, ein zusätzliches VHF-Funkgerät oder Satellitentelefon für die Gruppe mitzunehmen, zusätzlich zu dem inReach, das üblicherweise jemand anderes hat. Wenn wir nicht in der Lage gewesen wären, an den inReach des vergrabenen Skifahrers zu kommen, hätte das unseren Tag kompliziert, da wir mehrere Stunden von der Straße entfernt waren.

A couple of Avalanche Associations reached out to me and asked about what I thought the importance was of watching the snow where I thought the buried skier was while the snow was still sliding. I thought this was critical to our timing in finding her, as there wasn’t much screwing around once we started searching and we were within 10m of her in the first minute or two because we had an idea of where she was buried.

In a 2012 study by Pascal Haegeli at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, which compares Canadian to Swiss survival rates based on burial times, it was shown that in Canada, as the burial time increases you are significantly less likely to survive an avalanche. That’s expected, and the overall window of survival is closer to 10-18 minutes. To me, this stresses the importance of finding your partner fast and I believe that watching the snow and having newer generation beacons attributed to this.

There were human factors that lead to our incident, and I think fully reading the forecast, including the written details could have changed what happened that day. Certainly, if I see Low/Low/Moderate again I won’t assume that everything is fine and I will read deeper into the avalanche bulletin.

I am considering carrying a second communication device more often in the future too. That might be too much gear for a light and fast alpine route, but for other routes I can see it making sense. I figure that I can carry an extra VHF radio or sat phone for the group, in addition to the inReach that someone else normally has. If we would not have been able to get to the buried skier’s inReach, it would have complicated our day being several hours from the road.

This may not seem apparent, but don’t rush getting to the buried skier and risk getting hurt as the rescuer. Without two rescuers in our scenario, the outcome would have been different. I was able to self-arrest on the icy layer but then fell the length of the slope. Falling probably saved us time getting to the buried skier, but this easily could have gone differently. I have heard of incidents where rescuers are above the crown with buried partners far below at the base of the slope. I think chatting about not taking the additional risk of getting hurt as the rescuer and how an additional injury can create issues in the rescue is warranted; we were lucky.

Having two fit rescuers and a good understanding of what to do once the snow stopped moving helped when everything went wrong. We were fortunate to pull off such a deep companion rescue. This avalanche will change a few things I do in the mountains going forward.

--Tim Banfield

Wähle die besten Bretter für dein Lieblingsgelände aus.

Von der Kletterwelt inspiriert, von Hand gefertigt – unsere Prints für Frühjahr 2026 erzählen ihre...

Von der Kletterwelt inspiriert, von Hand gefertigt – unsere Prints für Frühjahr 2026 erzählen ihre ganz eigene Geschichte.

Einfache Tipps zur Pflege und Reparatur deiner Steigfelle vom Reroute-Team.

Schau zu, wie Connor am Empath-Felsen in Kirkwood, Kalifornien, ein weiteres legendäres Testpiece abräumt.

Stell dir dein perfektes Outdoor-Outfit zusammen – egal ob strahlender Sonnenschein oder Schneesturm.

Black Diamond Athletin Angela Hawse ist eine Wegbereiterin für Veränderung.

Das brauchst du für jede Art von Skitouren-Abenteuer.

Stell dein Setup für die nächste Skitour perfekt ein.

Begleite BD-Athlet Yannick Glatthard tief in die Schweizer Alpen, während er seine Heimatberge mit guten...

Begleite BD-Athlet Yannick Glatthard tief in die Schweizer Alpen, während er seine Heimatberge mit guten Freunden teilt.

Begleite Dorian Densmore und Mya Akins durch eine weitere Wintersaison voller steiler Alaska-Spines, versteckter Backyard-Couloirs...

Begleite Dorian Densmore und Mya Akins durch eine weitere Wintersaison voller steiler Alaska-Spines, versteckter Backyard-Couloirs und tiefer Abenteuer in den Bergen.

Wir bringen Licht ins Dunkel, wenn’s um Stirnlampen geht.

Schau dir an, wie BD-Athlet Alex Honnold hoch über Tahoe beim harten Trad-Klettern alles gibt.